A Primer on Asian Horror- Part 1: The Trinity

After the positive feedback we received on my review of the Netflix original, Kingdom, a Korean horror drama, the boss lady and I thought it would be a cool idea to do a follow up piece on Asian Horror in general, a genre that’s come into its own since the turn of the century. A subject in and of itself that can’t be explained in just one measly article, I opted to turn into a three-part series. So, let’s start trying to tackle this kaiju sized topic, shall we? And for more on the review that started this whole wheel turning, check it out here

First, a disclaimer: As the inter webs can be a harsh, judgmental, and fickle place, I’d like to start by saying that I am by no means an Asian Horror expert, nor do I claim to know the ins and outs of this distinctly unique form of cinematic storytelling. I’m just a fan who’s writing this from my own experience and offering my own two cents worth.

Now, with that out of the way, I found myself wondering where would be the best place to start this journey into the realm of the bizarre, and yes, it gets very bizarre. Asian horror is nothing new after all, not since the likes of writer, director, and actor Sammo Hung’s Chinese horror comedy, Encounters of the Spooky Kind, hit screens way back in 1980. A mix of laughs, Kung Fu fights, and scares, Hung’s now legendary film included one of the most memorable depictions of Chinese folkloric monster, the Jiangshi or “hopping” vampire (the belief being that if a corpse were reanimated or a person undead, the stiffness of rigor mortis would allow them only movement by means of hopping).

But it wasn’t really until the late 90’s/early 00’s that there was what I refer to as a renaissance in Asian horror thanks to the likes of a few daring filmmakers from all over the Far East. But to understand Asian Horror, you have to first understand that it’s very different from horror here in the West. For one, they don’t really specialize in the slasher film or furthermore, the “killer on the loose” picking off helpless teens by means of some unique or clever method all while donning some kind of mask, costume, or disfigurement. Don’t get me wrong, the Japanese especially, have tons of films where innocent teenagers are getting picked off one by one. But in those films, the culprit is more than likely a ghost/spirit/apparition or other supernatural force. Which is the next thing one must understand when exploring Asian Horror. Oftentimes the focus is on the supernatural, the aftermath or impact of war, or the real present-day world, because come on, what’s more scary then the everyday people, places, and things we deal with on a daily basis? Asian filmmakers wear their influences on their sleeves because their culture is so interconnected with the spirit world and the brutality of wartime and organized crime.

So, I thought we’d kind of start in reverse, by highlighting three of these groundbreaking filmmakers who I feel are responsible for modern Asian Horror and it’s now common acceptance as a viable genre, each specializing in their own brand of unique storytelling. I’ll point out which film put them on the map (critically of course), which is my favorite, as well as some of their other work worth checking out.

Again, kind of starting in reverse with the granddaddy of them all:

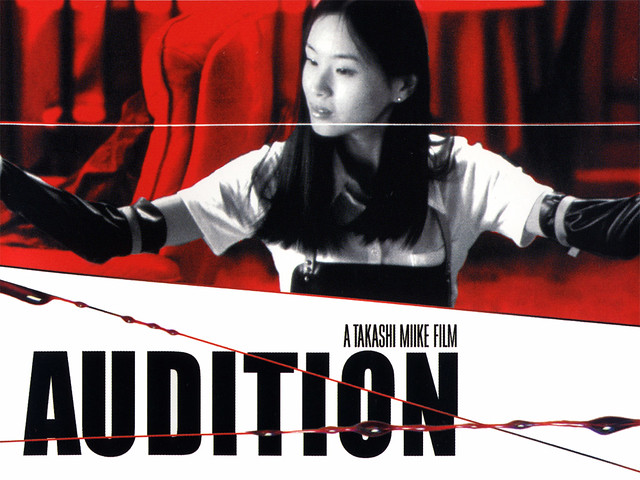

Takashi Miike – Japan:

Miike-san belongs on the list for easily being the most prolific of the three, having cranked out as many as 100 films already in his short career that started in the 90’s, with some years consisting of three or four releases in one single year. Also, easily the most versatile of the other members on this list with films covering the gamut of subject matter from period pieces, to crime-dramas, to children’s movies. But Miike-san was initially recognized, for better or worse, for his work in the twisted tales such as 1999’s Audition and 2001’s Ichi the Killer. The former is like the date film from hell! In it, a widower “auditioning” a future wife comes across the wrong girl who becomes jealous of the love he still holds for his dead wife and so, proceeds to paralyze him with a mysterious agent, but keeps his nerves active. Thus, the deranged Asami proceeds to torture the helpless Aoyama in the brutal third act. The film includes such imagery as vomit eating, mangled canines, and feet being sawed off with wires. And that’s just a taste. (It also made the Horror Essentials list, which you can check out HERE)

In Ichi, adapted from a manga by the same name, the title character is a psychologically damaged individual who is being manipulated by a Yakuza cleaner to take out rival gang members. But the real star of the film is Yakuza enforcer, Kakihara, played by Tadanobu Asano, whose jaw and mouth are held together by a piercing that can be removed to allow Kakihara to resemble some kind of snake, ready to devour prey. I believe this film alone, launched Tadanobu’s career into the stratosphere, appearing afterwards in all manner of Japanese film and television, as well as a few stints in some American films (but more on that in part 3 of my series). Like many of Miike’s early works, the film revolves a lot around the Japanese underground and its gangster culture, again, with the horror aspect really coming in the form of its brutal visuals. To this day, Ichi the Killer is banned in three countries.

Some of my other favorite films in the Miike library include the Dead or Alive trilogy, the first of which Joe Bob Briggs screened during his Thanksgiving Dinners of Death marathon last year. The only real connection across all three films though is the cast of characters, but the climactic ending of the Series in act 3 of Dead or Alive: Final, goes places no viewer could ever have guessed. If you have the stomach for it, also check out Visitor Q, which contains themes of incest, bullying, and dismemberment. But don’t fret, 2004’s family friendly Zebraman is a fun filled superhero comedy that actually spawned a manga from its screenplay (and not vice versa as with so many other Japanese fare), as well as a sequel six years later entitled, Zebraman 2: Attack on Zebra City. Lastly, if you want to see Miike-san at his best, in terms of a serious filmmaker, away from all the shock and controversy, then you must seek out his 2010 opus, 13 Assassins. And if that name sounds familiar, it’s because it was a remake of the 1963 classic of the same name. I had it on my radar for many years because a.) I love big budget Asian period pieces involving samurai or other forms of ancient and honorable warriors b.) I like Takashi Miike and c.) I had to see Takashi Miike doing a big budget Japanese period piece! It is sooooo good, people.

Park Chan-Wook (also credited as Chan-wook Park) – Korea:

Chances are, whether you knew it or not, you’ve heard of Park Chan-Wook’s work through his wildly popular 2003 film, Oldboy, which is actually the second entry in Wook’s Vengeance trilogy, with the first being Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. Definitely more along the lines of thriller than horror, Wook’s films explore deeply the human element of characters and the things they are capable of when pushed to the limit, although most of the time, it backfires on them in some manner at the end. Although he does three films about revenge, the story he’s really telling is that it can be all consuming and left in its wake, revenge can sometimes leave one with more bitter consequences in the fallout than originally thought. In a word, vengeance solves nothing.

Crediting Hitchcock for sparking his interest in pursuing a life in film, Wook’s work has reaped similar accolades in the industry. More of a filmmaker’s filmmaker than the previously mentioned Miike, Wook’s work has not only received critical acclaim in the form of various awards, including two separate wins at Cannes, one for the aforementioned Oldboy and 2009’s Thirst, but fan praise as well, with one of his biggest flag-bearers coming in the form of quirky auteur, Quentin Tarantino.

Speaking of Thirst, decidedly the most “horror” entry in his short career (in terms of bodies of work, not length), it tells the story of a priest, so dedicated to humankind, that he volunteers to be a test subject on a vaccine for a deadly virus. When the vaccine fails and he must receive a blood transfusion to survive, it turns out that the blood is from a vampire and as such, turns him into a vampire. Now with a thirst for blood and flesh, he must go against everything he stands for just to make it through. Once again, a story about humanity and the lengths at which we will go when absolutely necessary. These are the narratives that Wook thrives in.

Ryuhei Kitamura – Japan:

Of the three, Kitamura is my personal favorite because his style is a little more traditional, and a hell of a lot more action oriented. If the previous two directors are a little out there for you, I recommend Kitamura’s filmography because there is definitely more of a western influence that is easily visible in most his films. After all, Kitamura has stated in interviews that his dream project would be to direct an installment in the Mad Max franchise, and of the three has had the most visibility here in the states. But we’ll get more into that in the final part of my series.

Kitamura’s most notable film and the one that broke him into mainstream success in Japan is of course 2000’s Versus (are we seeing a pattern here in terms of dates yet?). Essentially a modern-day zombie film with distinctly Asian flair, Versus tells the story of a forest that is the 444th portal to the other side (of 666 of course) that, as a result, has the power to resurrect the dead. Once our protagonist, an escape convict who enters the forest fleeing imprisonment, bumps into a gang of Yakuza who are in there searching for a girl who has escaped their own clutches, chaos ensues. If you can make it through the bizarre intro which sets up the world the rest of the film takes place in, you will be in store for some great swordplay, gore, and gunplay.

The gore and swordplay continue in Kitamura’s period piece Azumi, released just 3 years later. Although more a revenge film than anything else, Kitamura’s skill is noticeably improved, especially in the climactic fight scene between Azumi and master swordsman Bijomaru. The cinematography and camera movement are spectacular! Speaking of great direction and even greater production design, check out Kitamura’s take on the iconic kaiju in 2004’s Godzilla: Final Wars released to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the main monster as well as meant to be the final Godzilla film (hence the name) in the franchise. Kitamura gets to direct almost every monster to ever appear in every Godzilla film ever released, including a jab at 1998’s Hollywood produced and Matthew Broderick starring Godzilla. Not to be outdone by previous releases, in Final Wars Kitamura shoots quite the frantic and action-packed motorcycle bridge sequence, reminiscent of early John Woo. We’ll be talking more about Kitamura in part three of my series: When East meets West.

Bonus Content:

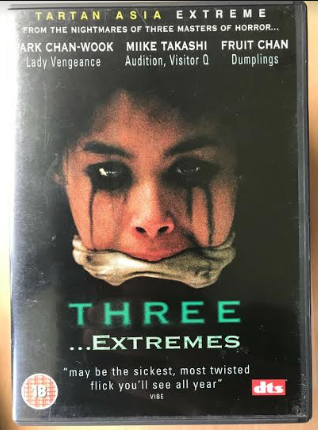

If you really want to blow your mind, check out 2004’s Three… Extremes, wherein two of the filmmakers I just spent 1500 words talking about join with Chinese director Fruit Chan to create one of the most terrifyingly peculiar horror anthologies. Capitalizing on the popularity of Asian horror, Three… Extremes took one promising filmmaker from each of the three largest markets, China, Japan, and South Korea, and had them each create a short to be included in the larger work. Miike, Wook, and Chan each take a turn at telling some of their most “extreme” stories, complete with shocking imagery, visceral gore, and torturous set pieces (quite literally;). Surprisingly, the standout of the three: Fruit Chan’s Dumplings.

So, there you have it, ladies and gents, my look at some of the most influential filmmakers in Asian horror. Although we may not agree on their definitions of horror or what they’ve accomplished since the horror genre put them on the map, there is still no doubt these three are heavily responsible for pushing the genre in their respective countries to the forefront and finally getting it into the mass market globally. We thank them all. Up next, in part two of my series, we’ll take a look at some of the genres, some other notable creators, and just some other great films in general you should be checking out.

Want more series like this? Just search below: