They’re Alive! The Bloodthirsty Babies of Larry Cohen

If we can agree on one thing about horror, it’s that things get exponentially creepier when kids are a part of the narrative. Whether it’s a demon-possessed tween, a little girl trapped in the ether by a spooky entity or toddlers who see ghosts and draw really aggressive circles over and over again, making a child the center of the horror cinematic experience really ups the ‘I am uncomfortable’ experience for the viewer. However, most kids in horror films are not particularly made to look any scarier than normal kids look (looking at you, Children of the Corn).

Sure, they look spooky, but they definitely don’t fall into the category of ‘grotesque’ (think Seth Brundle in The Fly or Edward Pretorious in From Beyond). The majority of possessed and paranormal-conduit children, even the murderous ones, tend to continue to appear child-like. Maybe their rosy cheeks will pale, their eyes will sallow and their hair will thin, but we the audience can always identify them as little Jimmy or little Sarah from up the road.

There are some films out there that took the idea that children must remain in an innocent physical state and threw it in the bin, a burning bin, and gave us some of the most horrifying images of children to date, children who no longer looked like children, whose bodies changed as their psyches did. This is more common with adult characters in body horror cinema. Its no big deal to watch Officer Eric’s head explode in Beyond the Gates, but there is something about watching a living-dead baby burst into flames that leaves a much deeper impact on the audience than watching this happen to a grown adult. This is perfectly sensible, of course.

Yet in the ‘70s through to the mid ‘80s, showing evil kids that exhibited visceral changes to reflect their inner evil didn’t rub too many movie-goers the wrong way. Upset over The Exorcist wasn’t about Linda Blair’s pus-filled bubbling mouth sore make-up and bloody facial-gouges, it was about possession and the potential reality of paranormal evil.

After watching a ridiculous amount of body horror, I realized that showing babies in gory scenarios was once quite acceptable, but as America’s social issues were juggled about, it became somewhat ‘taboo’. Although the sub-genre is said to have not appeared until the mid-1980’s, Larry Cohen’s blood-thirsty babies of the It’s Alive trilogy predate the come-uppance of body horror cinema, as does the severely grotesque Regan MacNeil in The Exorcist.

The first film in Larry Cohen’s trilogy, titled It’s Alive (1974) was released the year big changes in the United States were being made regarding women’s rights. The passing of Roe v. Wade, the bill that allowed women more autonomy over their bodies and sexual health, took place in 1973. It is hard not to draw a link between Cohen’s films about pregnancies gone wrong and killer babies and the political state of America. Cohen is known for making broad social commentaries in his films, and It’s Alive is no different.

In the film, a baby is born to Lenore and Frank Davis, a mutated baby with a hunger for human flesh. Immediately after birth, the Davis baby racks up a huge body count, viciously murdering everyone in the delivery room except his mother. He escapes, crawling through hospital vents and hiding behind waiting room ferns made of plastic, looking for his next victim. And oh, how many victims he finds! Yet the victims don’t matter, not to Lenore, who only wants her son to return home, her grotesque, vampiric ninja-turtle-toed son that she loves so deeply. The Davis Baby does come home to his loving parents who must take his life or watch him be slaughtered by law enforcement. Frank Davis shoots his own son, despite his unconditional love for the creature. This pushes the audience to ask themselves, is this truly a baby, or is it a monster?

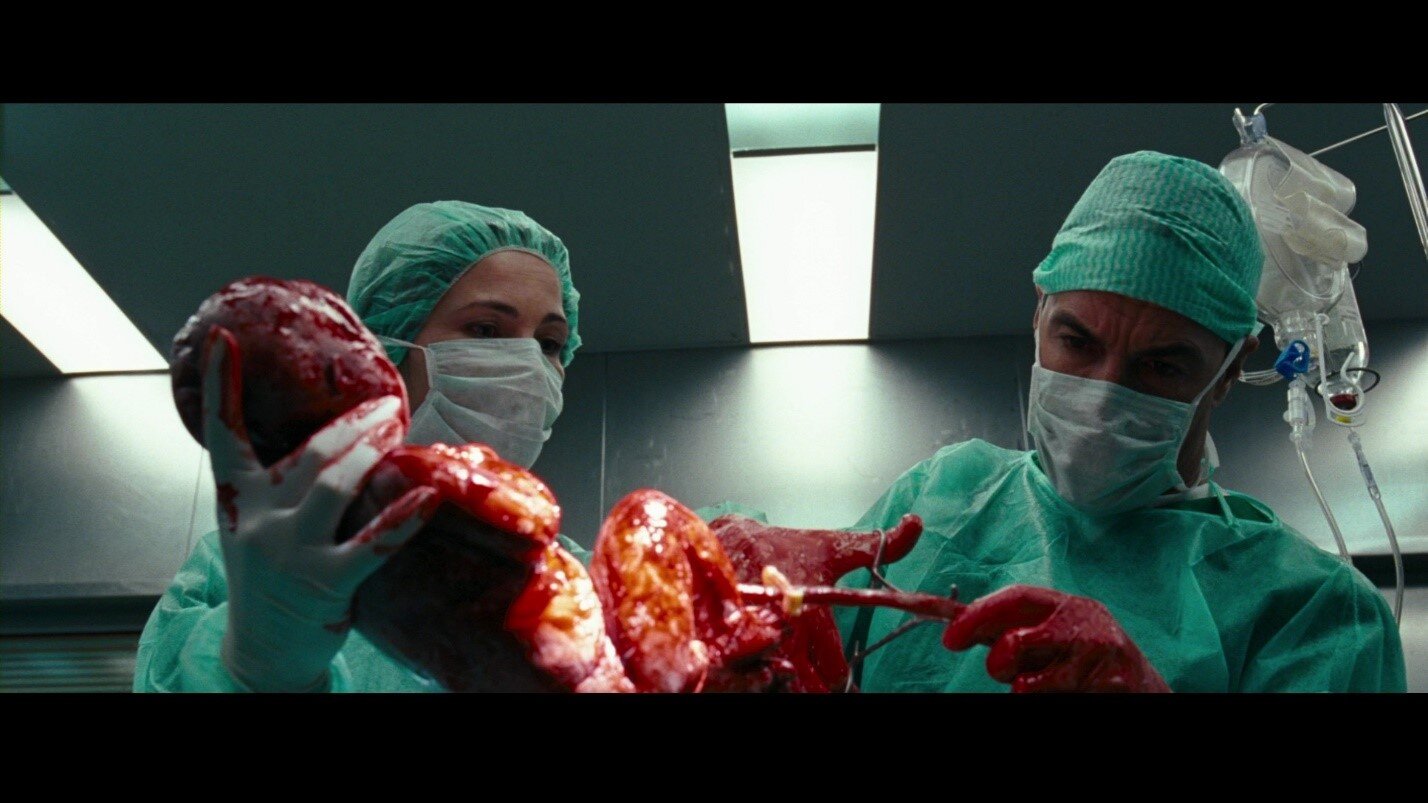

And how, you ask desperately, did this baby become a toddling mutant on a killing spree? All three of the films suggest the cause for the mutation, and it traces back to pharmaceuticals. Whatever the drug is, it has mutated these babies beyond recognition. The acts of violence committed by the babies in the first film are brutal, and you can see most attacks quite clearly. Clawing, biting and gutting scenes all make it clear that a blood-soaked infant is really going to town on that guy’s head. There is something exceptionally nightmarish about a baby in the role of the monster, and Cohen provided us with so many of them.

In 1978, Cohen released It Lives Again, the second installment in the It’s Alive trilogy. In this film, Frank Davis returns and has taken it upon himself to warn other expecting couples that they too may have evil mutant children that eat cats and milkmen, and that the government is coming for them. As it turns out, a group of kooky doctors have decided to study the mutant babies, educate them and allow them to bloom to their full potential. Alas, the babies do escape and have a good old ‘purge’ in town, one noticeably less gory than the first. Don’t get me wrong, there was plenty of blood, but the babies were shown less and less committing heinous acts. Many of the scenes mirror the milk-man scene from the first film, when you never see the attack, only a delectable mixture of blood and fresh buttermilk dripping from the back of the truck. We know what the babies are getting up to, we just aren’t as privy to the gore as we were before.

Almost 10 years passed before the world was gifted the incredible Island of the Alive (1987), the third installment of the It’s Alive trilogy. This film is significantly less grotesque than the first two when it comes to baby attacks on unsuspecting adults. Not only is there less focus on the babies themselves and more focus on the narrative of Jarvis, played by Michael Moriarty, who happens to be the father of a mutated baby just like Frank Davis.

What this film lacks in gory baby attacks, it makes up for in grown up baby attacks! Yes! The babies have all been dumped on a deserted island to live in the wild and let evolution take its course. Seeing as these infants grow and age at an accelerated rate, by the time Jarvis and a team of scientists travel back to the island to check on their little experiment, and for Jarvis to retrieve his son, the It’s Alive babies are fully grown adults (who look horrifyingly like giant toddlers). So fully grown in fact that two of them made an extra scary mutated baby of their own (yikes, right?) thus allowing the audience a sigh of relief that they don’t have to watch kids kill anyone anymore.

What is scarier than being chased by a psychotic scalpel wielding Gage fresh from the Sematary? Nothing, because it all comes down to morality. As adults, the image of you defending yourself against a peer is easy enough to conjure in order to come up with a plan in case you spot Michael Myers across the parking lot of the 7/11. But fighting a baby? That takes some serious calculation and the ability to question your own morals and need for survival. This is often why the grotesque, murderous infant is so effective in horror cinema. Seriously, how do you bring yourself to do whatever it takes to survive a deadly vampire baby attack, especially if they are kind of cute?

An increase in censorship from 1975 when the original film was released to 1987 when the third hit the theaters is noticeable. The grown-up mutant babies can now attack whoever they want wherever they want on camera. They can be shown in more than flashes as they menacingly approach their next victim, because we have completely disassociated them from the idea of childhood and innocence. Now you can imagine yourself fighting the enemy without moral quandary, and if my gut is correct, this feeling is a unique reaction to America in the mid ‘80s and the treatment of children.

Before 1980, children were mostly regarded as smaller adults. Times were different and the attention and care we give to children now was not as common practice back then. Shortly before the final film in Cohen’s trilogy, a shift in society’s views on children and childhood occurred, and suddenly the well-being of children was becoming a priority. The faces of missing children began appearing on the sides of milk cartons and suddenly everyone started to care a little more. Children were given ID cards in schools and many people started locking their doors.

Could this societal shift have anything to do with the decrease in bloody baby attacks as the trilogy progressed? It may sound farfetched, but Stephen King and Mary Lambert’s Pet Sematary (1989) hit a multitude of walls before and during production because the death, resurrection and subsequent ‘bad’ behavior of Gage was too gruesome, too cruel, and inappropriate for the audience (there is a phenomenal documentary on this called Unearthed and Untold: The Path to Pet Sematary, check it out!). I can imagine something similar possibly happening to Larry Cohen. If this still seems far-fetched, then maybe the 2008 remake of It’s Alive will put the nail in the coffin. The first one, anyway.

Joseph Rusnack’s remake of the original 1975 film is wildly different from Cohen’s in so many ways, one of them being, that’s right, the stark differences in gory baby murders. In Rusnack’s version of the film, the mutant baby does not look like a mutant at all. In fact, he looks just like a normal newborn, if a bit ugly. As in the original, the baby is born, and everyone in the delivery room is slaughtered, but in this version, you see nothing but a shot of the newborn sleeping on Lenore’s belly, surrounded by blood and bodies. Every gory scene after this is presented in a similar way.

The baby goes home with Lenore and her boyfriend and everything seems fine until dead half-eaten animals start showing up around and inside of their home. This is of course the work of the new Davis baby, but we never really see him consume an animal for more than a split second. Out of all his human victims, only one attack can be clearly seen onscreen, yet we never see the baby’s face. Despite the excellently excessive blood and guts in the remake, there is a clear chasm between the baby and the grotesque, a seeming censorship of the gore in the original film to fit the current audience. Fascinating how these things change.

There has never been another film quite like Larry Cohen’s It’s Alive. Sure, it is a creepy creature feature with the perfect amount of guts and gore and visceral mayhem for the sub-genre, but it’s also a bit more than that. It’s a commentary on family, gender roles, government conspiracies and so many other timely issues. The trilogy is also a phenomenal example of how horror cinema mirrors the ebb and flow of social norms and expectations and either caters to them or breaks them. As the 2010’s ended and the 2020’s begin, things have begun to change again. Directors like Ari Aster (Hereditary, 2017) and Cary Murnion (Cooties, 2014) have been slowly pushing the boundaries of what the audience can handle when it comes to children and the grotesque. Might a new wave of horror films bring back infant monsters like the ones in It’s Alive? Or is the world not ready for another Davis Baby?

Don’t want to miss anything on the site? Sign up for our newsletter HERE

Want more spine chilling children? Just search below: